The Beijing-Shanghai project will form the backbone of the nation’s quantum communications network

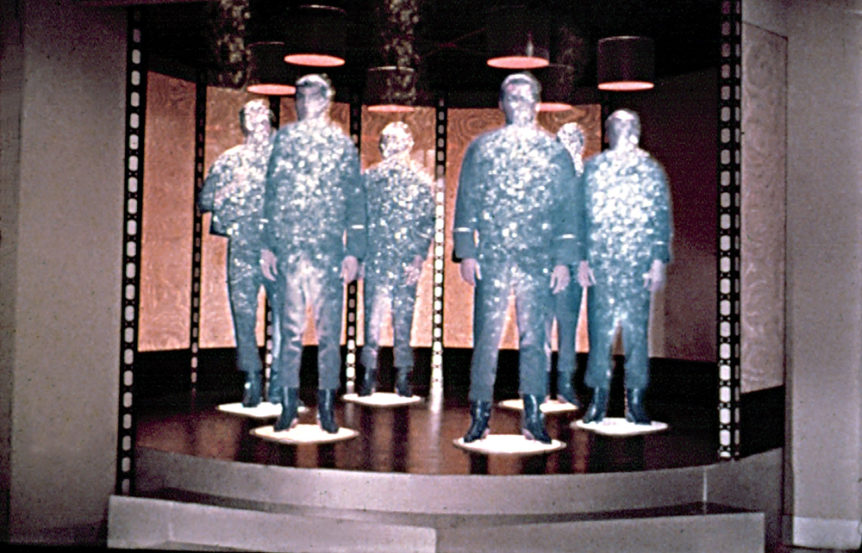

Quantum Space Link: Staff work on China’s quantum research satellite, which launched in August. It is part of a larger effort in the country to push the limits of quantum key distribution.

By the end of this year, a team led by researchers from the University of Science and Technology of China, in Hefei, aims to put the finishing touches on a 2,000-kilometer-long fiber-optic link that will wind its way from Beijing in the north to the coastal city of Shanghai.

What will distinguish this particular stretch of fiber from myriad other long-distance links is its intended application: the exchange of quantum keys for secure communication—a sophisticated gambit to protect data from present and future hackers. If all goes according to plan, this Beijing–Shanghai line will connect quantum networks in four cities. And this large-scale terrestrial effort now has a partner in space: A quantum science satellite was launched in August with a research mission that includes testing the distribution of keys well beyond the country’s borders.

With these developments, China is poised to vastly extend the reach of quantum key distribution (QKD), an approach for creating shared cryptographic keys—sequences of random bits—that can be used to encrypt and decrypt data. Thanks to the fundamental nature of quantum mechanics, QKD has the distinction of being, in principle, unhackable. A malicious party that attempts to eavesdrop on a quantum transmission won’t be able to do so without creating detectable errors.

QKD has already made its way into the real world. In 2007, the scheme was used to secure the transmission of votes in a Swiss election. Several years ago, the U.S.-based firm Battelle began to use the approach to exchange information securely over kilometers of fiber between its corporate headquarters in Columbus, Ohio, and a production facility in Dublin, Ohio.

But despite great progress, there has been a stumbling block to wide distribution. “The problem we’ve got is distance,” says Tim Spiller, director of the United Kingdom’s Quantum Communications Hub, a nationally funded project that is building and connecting quantum networks in Bristol and Cambridge, in England.

The challenge is that QKD encodes information in the states of individual photons. And those photons can’t travel indefinitely in fiber or through the air; the longer the distance, the greater the chance they will be absorbed or scattered.

This characteristic has a direct impact on how quickly a quantum key can be generated, explains physicist Jian-Wei Pan, who leads the Chinese projects. If researchers attempted to send signals directly down 1,000 kilometers of fiber, Pan says, “even using all the best technology, we would only manage to send 1 bit of secure key over 300 years.”

Instead, QKD fiber links must have a way to refresh the signal every 100 km or so to maintain a reasonable bit rate. But this can’t be done with conventional telecommunications equipment. The same rules that protect quantum transmission against eavesdropping also prohibit a quantum key from being copied without corrupting it. The solution has been to concatenate, creating a daisy chain of individual quantum links connected by physically secured spots, or “trusted nodes.” Each intermediate node measures the key and then transmits it with fresh photons to the next node in the chain.

The Beijing–Shanghai line will use 32 trusted nodes to create the 2,000-km line. This approach isn’t ideal for security. Because each trusted node has to convert the quantum key back into classical (nonquantum) information before passing it on, an eavesdropper at the node could potentially hack the data stream there undetected. “That’s the drawback,” Pan says. But the approach is “still much better than traditional communications… [where] there is the possibility of performing eavesdropping” at every point along the route, he says. Here, the problem is limited to 32 spots under lock and key.

“A long-distance chain link like this, [it’s] really the first time it’s been done,” says Grégoire Ribordy of ID Quantique, based in Geneva, which makes hardware for QKD networks. “It’s inspiring other people to try to do similar things around the world.”