A new Silk Road planned by China could cost $100 billion and reach 63 percent of the world’s population.

Kate Drew, special to CNBC.com

China is moving to revitalize the ancient Silk Road trade route, and its plan runs through a nation that has bedeviled both the U.S. and Russia for decades: Afghanistan.

In 2011, the U.S. unveiled a plan for a New Silk Road that would help Afghanistan strengthen relationships with its neighbors through resumed trading routes and the rebuilding of critical infrastructure. It was supposed to promote stability in the region after the U.S. began to withdraw its forces. Two years later China announced its own blueprint for the long-defunct trade corridor, called the Belt and Road Initiative, and according to foreign policy experts, China’s ambitions are now plowing right over the U.S. plan.

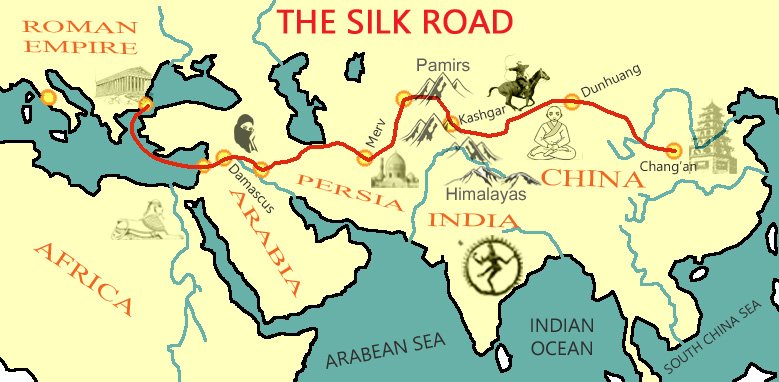

China’s initiative is two-pronged. The Silk Road Economic Belt is the revived land network connecting Asia, Europe and Africa, while the 21st Century Maritime Silk Road is an economic passageway running through the Pacific and Indian oceans. Together, the two amount to a set of free trade agreements and infrastructure projects that reach 4.4 billion people, or 63 percent of the world’s population.

China seems willing to spend heavily to promote its plan.

Dr. Zhiqun Zhu, a professor of political science and international relations at Bucknell University, said the high-end estimate is that China spends 14 to 15 times the cost of the Marshall Plan, with inflation. The Marshall Plan cost about $13 billion in 1950, which translates to more than $100 billion in 2015.

While the estimated cost is high, one potential prize among Silk Road riches are undeveloped mineral resources in Afghanistan, worth a reported $1 trillion.

“It’s a very rich country when it comes to mineral resources,” said Jack Medlin, program manager at the U.S. Geological Survey.

Afghanistan’s mineral deposits include an estimated 1.4 million metric tonnes of rare earth elements (REEs), such as lanthanum, cerium and neodymium.

Such deposits, buried deep in the land that was at the core of the U.S. Silk Road plan, are used widely in the making of cellphones, cameras, cars, wind turbines and computers, among many other technology products.

China’s rare advantage

“It would be too bad if China ended up with all the rare earth minerals that are apparently in Afghanistan,” said a former senior Obama administration official who has worked on relationships in the Asia region.

That’s because China already maintains a virtual stranglehold on the REE market, controlling more than 90 percent of production and consuming over 60 percent of it, according to various market research firm estimates. China has used this near-monopoly to manipulate the global market for rare earth elements in the past, slowing and, on occasion, even halting production, leading to supply shortages around the world and steering government-backed U.S. researchers to look for laboratory replacements for naturally occurring REEs.